Civil War Journal

SGT Christopher Columbus Harbison of Harrisonville, New Jersey

48th Infantry New York

1861-1864

United States of America In Flux

In February 1861, the United States of America consisted of both slave supporting states and free states. It was extremely difficult to forecast what it would be like in five years, just short of its one hundred year anniversary. The newly formed Republic Party nominated Abraham Lincoln to be president of the United States. The party platform, which President-elect Lincoln resolutely supported, prohibited the extension of slavery into any new territory. Many slave states were offended by this policy and feared that other federal policies would threaten their livelihood and way of life. Before President-elect Lincoln was inaugurated, seven deep south cotton states seceded from the United States and formed the Confederate States of America. Other states watched to see how the new federal government would respond. The Confederate States sent emissaries to negotiate for the surrender of federal forts and other federal installations within the seceded territory, offering to pay for them. However, the United States did not recognize the secession and refused. The Confederacy then forcibly took control of several unmanned forts and other federal installations, including numerous armories.

Four forts in the terrritory claimed by the Confederates remained in federal control. Fort Taylor in Key West and Fort Jefferson in the Dry Tortugas were too remote to be of major importance to the Confederates. However, Fort Pickens at the entrance to Pensacola harbor in Florida and Fort Sumter within Charleston Harbor of South Carolina were areas of intense focus. Until this time, an informal truce had been in place between the Confederates and President Lincoln's predecessor, President Buchannan. There would be no hostilities as long as the forts were not supplied and reinforced. Now the people of the United States and the Confederate States waited to see the direction that the new government would take.

After his inaguration, the new president faced a Southern Confederacy, a federal fort surrounded by scores of guns in the South Carolina swamps, a hopeless peace convention, and a new Republican party that consisted of a collection of numerous factions with their own agendas. President Lincoln did not decide immediately upon a federal response to the fort question. Eventually, he decided to resupply and reinforce the forts. Fort Pickens on the seacoast was readily accessible for reinforcements and supplies. However, Fort Sumter, within the Southern controlled harbor, was much more difficult to supply without triggering a war. The Confederates understood this. In April, Secretary Walker of the Confederate States sent General Beauregard instructions that if the United States attempted to reinforce Fort Sumter, he was to demand immedate federal evacuation. If that was refused, he was to "reduce it". On April 12, 1861 the bombardment of Fort Sumter began. Three days later, the garrison surrendered. The Civil War had begun.

Enlistment

Union and Confederate forces prepared for what each side assumed would be a short war following the fall of Fort Sumter. On April 15, 1861 President Lincoln issued a proclamation, known as "Lincoln’s Call for Troops", that called for seventy-five thousand militia to serve for three months in order to suppress the southern rebellion. In response, New York provided over thirteen thousand militia.

On May 3, 1861, the President called for an additional thirty-nine regiments of volunteer infantry and one regiment of calvary to serve for "three years unless sooner discharged". No quota was assigned to the states for the requested forty-two thousand men, but the Governor of New York called for twenty-five thousand volunteers. During the total duration of the Civil War, nearly four hundred thousand New York volunteers joined the Union Army, ranking New York first in the number of soldiers serving, followed by Pennsylvania, Ohio, Illinois and Indiana.

The first battle of the Civil War occured in July 1861 at Bull Run (Manassas Junction, Virginia). It was recognized after the Union defeat that the war was not going to be short.

There is nothing in American military history quite like the story of Bull Run. It was the momentous fight of the amateurs, the battle where everything went wrong, the great day of awakening for the whole nation, North and South together. It marked the end of the ninety-day militia, and it also ended the rosy time in which men could dream that the war would be short, glorious, and bloodless. After Bull Run, the nation got down to business. (Catton, New History of the Civil War, pg 78)

Congress, in acts of July 22, July 25, and July 31, 1861, authorized the President to accept the services of additional volunteers for three years in such numbers, not exceeding one million, as he might deem necessary for the purpose of repelling invasion and suppressing insurrection. They provided funding in 1862 by passing the first income tax law. Foreshadowing our modern income tax, it was based on a graduated withholding of income at the source. A person earning between $600 and $10,000 per year was taxed at three percent. Those with higher incomes paid taxes at a higher rate. In addition, sales and excise taxes were collected, and the “inheritance” tax made its debut.

As part of the war effort, the War Department authorized Colonel James H. Perry on July 24, 1861 to recruit a regiment of infantry from the area near Brooklyn, New York. Recruiting posters enticed men with patriotic appeals, enlistment bonuses and promises of well supplied units with experienced officers. The resulting 48th Infantry of New York consisted of volunteers from different areas as follows: Companies A, C, G and I were from Brooklyn; Company B from Brooklyn and Peekskill; Company D (a.k.a. "Jersey Company" and "Die-no-mores") from New Jersey; Company E from Brooklyn, New York City, New Jersey, Massachusetts and Connecticut; Company F from Brooklyn and New York City; Company H from Brooklyn and from Monmouth County, New Jersey; and Company K from Brooklyn and Galesville.

As part of the war effort, the War Department authorized Colonel James H. Perry on July 24, 1861 to recruit a regiment of infantry from the area near Brooklyn, New York. Recruiting posters enticed men with patriotic appeals, enlistment bonuses and promises of well supplied units with experienced officers. The resulting 48th Infantry of New York consisted of volunteers from different areas as follows: Companies A, C, G and I were from Brooklyn; Company B from Brooklyn and Peekskill; Company D (a.k.a. "Jersey Company" and "Die-no-mores") from New Jersey; Company E from Brooklyn, New York City, New Jersey, Massachusetts and Connecticut; Company F from Brooklyn and New York City; Company H from Brooklyn and from Monmouth County, New Jersey; and Company K from Brooklyn and Galesville.

Company D was organized by Captain D. C. Knowles. Prior to the war, Captain Knowles was both a language teacher at a seminary at Pennington, New Jersey and a clergyman. To prepare himself for his new role, he studied military tactics, rules of war and army regulations.

In August 1861, during one of Captain Knowles recruitment drives through southern New Jersey, Christopher Columbus Harbison, age 25 years and 3 months, responded to the request for volunteers. Christopher was a farmer from Harrisonville and stood five feet seven and a half inches tall. He enlisted at Sculltown, New Jersey on August 26, 1861 as a Private for a period of three years. It was common to assign recruits from the same are to different companies. The following reflects the original assignments of men from areas around Harrisonville, New Jersey.

- Charles Micreaf from Harrisonville

- Charles W. Mounce from Harrisonville

- Henry Micreaf of Harrisonville

- John Nixon from Woodstown

- Elever Sounder from Swedesboro

- Henry Ware from Harrisonville

- Enoch Allen from Harrisonville

- John H. Graham from Sculltown

- Thomas McDowell from Harrisonville

- William H. McAulla from Harrisonville

- John Pimm from Harrisonville

- Edward Sibley from Harrisonville

- James Spears from Woodstown

- Jacob Z. Hult from Harrisonville

- Aaron Coles from Harrisonville

- Aden Lippincott from Harrisonville

- Levi Pimm from Harrisonville

- Christopher C. Harbison from Sculltown

- Thomas M. White from Woodstown

- Stacy K. Duffee from Harrisonville

- John Keen from Woodstown

New York regulations required each regiment of infantry to be comprised of ten companies. Each company was to have between 83 and 100 men. The 48th Infantry was mustered into service between August 16 and September 16, 1861.

Company F, into which Christopher enlisted, began their service on August 31, 1861 at Camp Wyman near Fort Hamilton, New York. The men were mostly from New York and Brooklyn. The regiment left New York September 17 aboard the steam ship John Potter and steamed from Staten Island Sound to South Amboy, New Jersey. The men then took the train to Philadelphia, Pennsylvania where they received a hearty meal courtesy of the city on their way to the front. They continued on by train to Baltimore, Maryland where, because there was not a direct rail connection though the city, the troops had to march ten blocks between the stations on their way to Washington, D.C.

The city of Baltimore was a place of tension ever since April 19, when local Southern sympathizers had clashed with Northern militia on their way to Washington. Some Union soldiers were killed in the ensuing riot. Subsequently, many troops marched through the city with loaded rifles. Fortunately, the public left the 48th Infantry undisturbed. No enthusiastic greeting or insults met them as they marched. By 6 o’clock on September 18, they reached Washington. There they camped on Washington Hill and drilled for many weeks, preparing for the upcoming campaigns.

Sometime before October, Christopher transferred to Company D where he could be with other men from Harrisonville. The men of Company D, known as the” Jersey Company”, had similar backgrounds to Christopher. Of the original 87 officers and enlisted men, 78 were American born and 58 were natives of New Jersey. There were 47 farmers, 23 mechanics, 9 teachers and students, and 8 merchants. The average age at enlistment was 21 years and 8 months. The average height was five feet, six and a half inches.

Christopher Harbison enlisted as a private, was promoted to Corporal and then on April 28, 1864 was promoted to Sergeant.

Hilton Head Island, South Carolina (1861 - 1862)

By July 1861, the federal government was blockading the southern seaports to prevent the Confederacy from importing guns, ammunition and supplies, as well as exporting commodities, especially cotton. The main challange was not actually blockading the major seaports, but resupplying the blockade ships. Because the federal government had no suitable bases in the South, the ships spent most of their time sailing between their blockade stations to either Maryland or New York for the needed coal and supplies. A supply base within the Confederate territory was desired. Port Royal Sound in South Carolina was chosen. Adjacent land would then be captured to secure the harbor.

By July 1861, the federal government was blockading the southern seaports to prevent the Confederacy from importing guns, ammunition and supplies, as well as exporting commodities, especially cotton. The main challange was not actually blockading the major seaports, but resupplying the blockade ships. Because the federal government had no suitable bases in the South, the ships spent most of their time sailing between their blockade stations to either Maryland or New York for the needed coal and supplies. A supply base within the Confederate territory was desired. Port Royal Sound in South Carolina was chosen. Adjacent land would then be captured to secure the harbor.

The Navy appointed Captain Samuel DuPont as Flag Officer. The War Department appointed Brigadier General Thomas W. Sherman to lead the troops. The gathering of ships and men, including Company D, began in August 1861 in Annapolis, Maryland.

At noon on October 5, 1861 Company D left Washington, D.C. for Annapolis, arriving at 11 p.m. They boarded the steamer Mayflower on October 18 and steamed for a few miles. They transferred to the steamer Empire City. On October 21, they steamed for Fortress Monroe, Virginia to rendezvous with the fleet. Gathering there were 12,653 men, 50 war vessels, 25 coal vessels, and several smaller crafts. The expedition sailed by October 29.

At noon on October 5, 1861 Company D left Washington, D.C. for Annapolis, arriving at 11 p.m. They boarded the steamer Mayflower on October 18 and steamed for a few miles. They transferred to the steamer Empire City. On October 21, they steamed for Fortress Monroe, Virginia to rendezvous with the fleet. Gathering there were 12,653 men, 50 war vessels, 25 coal vessels, and several smaller crafts. The expedition sailed by October 29.

On November 1, a violent storm off Cape Hatteras scattered the fleet. Once the storm passed, the men of Company D saw no other vessels. However, sealed orders had been given to each ship in the event of such a mishap which enabled the fleet to regroup by November 4 off of Port Royal Sound, South Carolina.

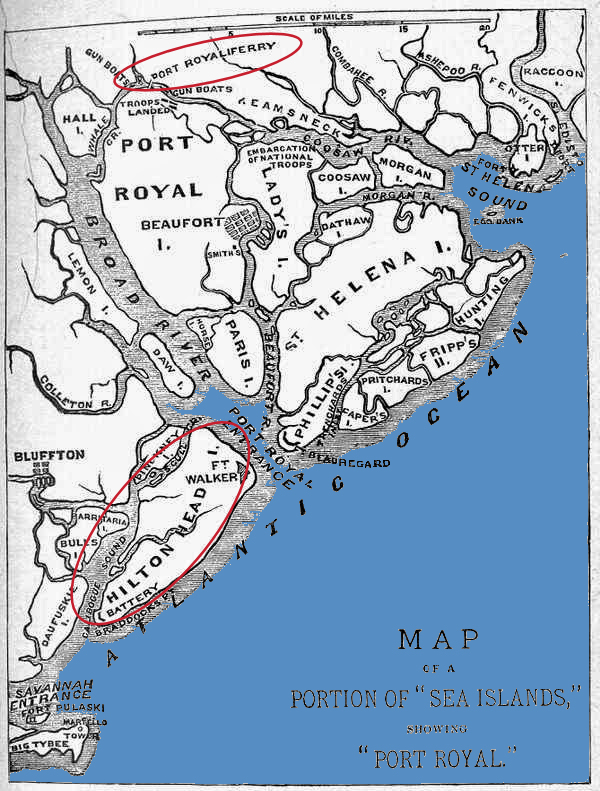

The two-mile-wide channel to the sound was guarded by two forts: Fort Beauregard on Bay Point to the north and Fort Walker on Hilton Head Island to the south. After furious exchanges of gunfire between the gunboats and the shore batteries on November 6 and 7, the Confederate soldiers retreated from their fortifications to take up positions further inland. A small fleet of Confederate ships retreated into the inland waterways.

The two-mile-wide channel to the sound was guarded by two forts: Fort Beauregard on Bay Point to the north and Fort Walker on Hilton Head Island to the south. After furious exchanges of gunfire between the gunboats and the shore batteries on November 6 and 7, the Confederate soldiers retreated from their fortifications to take up positions further inland. A small fleet of Confederate ships retreated into the inland waterways.

Company D landed on Hilton Head Island on November 9, 1861. The island provided the desired federal base in Confederate territory between Savannah, thirty miles to the south, and Charleston, sixty miles to the north. However, whenever Union troops attempted to move inland, General Lee’s army was able to drive them back. On Hilton Head Island, an unexpected problem arose when the Federals became stewards to a number of black communities left from abandoned nearby plantations. The question that the federal government wrestled with was what to do with this population. At this time in the Civil War they were not considered free. Eventually they were put to work at the nearby plantations in the area. Although the Union army did not extend the land conquest from the island, they used the island as an important base to supply their warships and blockaders of the Savannah River and Charleston Harbor.

On December 31, Company D embarked on a transport to drive out the only Confederate stand along the waterways in the area. Under the leadership of Colonel Perry and Lieutenant Colonel William Barton, the Confederate resistance was overcome at Port Royal Ferry on the Coosa River.

| Place | Date | Killed | Wounded | Missing | Total | |||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Died | Recovered | |||||||||

| Off. | Enl. | Off. | Enl. | Off. | Enl. | Off. | Enl. | |||

| Port Royal Ferry, S.C. | Jan 1, 1862 | 3 | 3 | |||||||

Savannah, Georgia (1862)

Now that a suitable base had been established, a campaign against Savannah, Georgia could begin. The Savannah River, which provides passage to that city, was guarded by Fort Pulaski. Fort Pulaski had to be taken in order to strenghen the blockade of the principal port of Georgia. The plan to capture Fort Pulaski included: constructing batteries upstream on both sides of the river to prevent supplies and reinforcements from reaching the fort during a seige and construction batteries on Tybee Isalnd that would be capable of firing on the fort.

Access from the ocean to the Savanah River above the fort and away from Confederate batteries could be obtained by way of New River, Wall's "Cut", and Wright's River. Wall's "Cut" was a man-made channel that allowed inland waterway passage between Charleston and Savannah. The Confederates had placed an old hulk and several heavy piles as obstructions into the "Cut". It took four days and four nights, until January 14, for the obstructions to be removed. The piles were sawed off at the bottom of the stream and the hulk was swung out of the way. The obstructions were removed by a detachment of Engineer troops, under Major Beard and 48th regiment New York volunteers. Union transports and gunboats could now use the passagway.

Company D, in which Christopher Harbison was enlisted, was detailed to assist with the construction of the northen battery, Battery Vulcan. So on January 25, they marched to Saybrook’s Landing on Hilton Head Island and set up camp in the woods on Dawfuskie Island.

On January 28, a reconnaissance was made of Jones Island. It was determined that a sutiable battery could be located at Venus Point, along the shore of the Savannah River. The best passageway to Venus Point from Mud River was about 1,300 yards through mud marsh.

Jones Island is nothing but a mud marsh, covered with reeds and tall grass. The general surface is about on the level of ordinary high tide. There area a few spots of limited area, Venus Point being one of them, that are submerged only by spring tides, or by ordinary tides favored by the wind; but the character of the soil is the same over the whole island. It is a soft, unctuous mud, free of grit or sand, and incapable of supporting a heavy weight. Even in the most elevated places, the partially dry crust is but three of four inches in depth, the substratum being a semi-fluid mud, which is agitated like jelly by the falling of even small bodies upon it, like the jumping of men, or ramming of earth. A pole or an oar can be forced into it with ease, to the depth of twelve or fifteen feet. In most places the resistance dimishes with increase of penetration. Men walking over it are partially sustained by the roots of reed and grass, and sink in only five or six inches. When this top support gives way, they go down from two to two and on-half feet, and in some places much more.

From February 1 through February 4, two engineer companies cut poles for the "causeway" on Jones Island and for a wharf on Daufuskie Island.

The wharf on Daufuskie Island was completed on February 4. By then 10,000 poles, five to six inches in diameter and nine feet long had been cut. The men of the 48th New York and 7th Connecticut volunteers transported the poles on their sholders to the wharf for a distance of about a mile. Approximately 1,900 were staged at the wharf for Jones Island.

On February 5th and 6th - Nothing specially new. Engineer force engaged in cutting poles, filling sand-bags on Daufuskie Island, building a temporarry wharf of poles and sand-bags on Mud River, and constructing a whellbarow track of planks laid end to end, from Venus Point to Mud River wharf. The 48th New York, 7th Connecticut volunteers, and a portion of the engineer forces, engaged in transporting poles and planks, and carrying filled sand-bags from Daufuskie Island to Jones Island (a distance of about four miles) in row boats.

February 7th and 8th - Finished temporary wharf on Mud River; carried several hundred filled sand-bags across to Venus Point; also, a quantity of planks and other building materials.

February 10th- ... It was determined to establish the Venus Point battery at once, and wait no longer for the gunboats to go ahead of us; also, to effeect this by landing the guns on Jones Island, from Mud River, and hauling them over the marsh, instead of towing them into the Savannah (with the Navy) in flats, as first contemplated. Major Beard, 48th New York Volunteers, and Lieutenant J.H. Wilson, Topographical Engineers, volunteered to assit Lieutenant Horace Porter, the ordance officer, in getting the flats into Mud River, and the guns on shore and into position. Accordingly, the flats with the guns were towed by our row-boats up the river, against the tide, and landed without accident. The 48th New York Volunteers furnished the fatigue parties, which had already been twenty-four hours at work on Jones Island, and were very exhausted.

During the night of the 10th, Lieutenant O'Rourke of the Engineers, with a party of volunteer engineers, commenced the magazine and gun platforms at Venus Point. The platforms were made by raising the surface five or six inches, with sand carred over in bags. On this sand foundation, thick planks, perpendicular to the line of the battery, were laid... At right angles to these, deck-planks were laid, giving a platform nine by seventeen feet.

February 11th - Continued getting battery and road materials to Jones Island during the day. Early in the evening I went to Jones Island, with fresh men, to finish the labor of getting the guns over. The work was done in the following manner: The pieces, mounted on their carriages and limbered up, were moved foreward on shifting runways of planks (about fifteen feet long, one foot wide, and three inches thick), laid end to end. . . Each party had one pair of planks in excess of the number required for the guns and limbers to rest upon, when closed together. This extra pair of planks being placed in front, in prolongation of those already under the carriages, the pieces were then drawn forward with drag-ropes, one after the other, the length of the plank, thus freeing the two planks in the rear, which, in their turn, were carrried to the front. This labor is of the most fatiguing kind. In most places the men sank to their kenees in the mud; in some places, much deepter. This mud being of the most slippery and slimy kind, and perfectly free from grit and sand, the planks soon became entirely smeard over with it. Many delays and much exhausting labor were occasioned by the gun-carriages slipping off the planks. When this occured, the wheels would suddendly sink to the hubs, and powereul levers had to be devised to raise them up again. I authorized the men to encase their feet in sand-bags, to keep the mud out of their shoes. Many did this, tying the strings just below the knees. The magazines and platforms were ready by daybreak.(Gillmore, pgs 14, 16 - 18)

According to the pension records of Christopher Harbison, he "contracted catarrh by exposure during this time. His associated skin trouble increased with age. His hands cracked badly and the skin broke and pealed. His liver trouble caused depression of spirits and irritation."

On February 14, 1862 three Confederate gunboats unsuccessfully attacked Battery Vulcan on the north shore of the Savannah River. One of the attacking gunboats was struck. Battery Hamilton also had been constructed along the southern shore across from Battery Vulcan. The Confederate gunboats retreated to Savannah and did not challange these batteries controlling the Savannah River again.

While Battery Vulan and Battery Hamilton were being constructed, eleven batteries were built on Tybee Island within range of Fort Pulaski. The Federals began the barrage of the fort beginning about 8 o’clock in the morning of April 10. The shelling continued throughout the night and ended about 2 o’clock the following afternoon. Throughout the bombardment, the Confederates took shelter within the fort in bombproofs. Although the fort had 40 guns, the masonry structure was no match for the penetrating shells that were fired. The 360 Confederate soldiers garrisoning the fort surrendered during the early afternoon of April 11.

The 48th Regiment, including Company D, was ordered from Dauwfuskie Island to the captured fort for garrison duty. They were fully moved and began garrison duty on June 1, 1862. The days of garrison duty were long and tedious. The fort was repaired. The men drilled at artillery. Mail arrived and stories were shared two or three times weekly. Many of the men learned trade skills. A theater group was formed that earned the name “Barton Dramatic Association."

Relief to the monotonous garrison duty was provided by brief skirmishes into Confederate territory. On September 21, about one-third of the regiment steamed up the river and successfully destroyed a section of the railroad and telephone lines. On September 4, Colonel Barton lead a skirmish at Skull Creek. On September 30, five companies of the 48th Regiment under Colonel Barton and Captain Strickland skirmished at Bluffton and Crowell’s Plantation near May River. On October 1, five companies under the same leadership skirmished on Elba Island, upriver from Fort Pulaski. On October 18, one company of the 48th skirmished at Kirk’ Bluff on the May River. It is not known what part Christopher had in these actions. Garrison duty continued until new orders were received.

| Place | Date | Killed | Wounded | Missing | Total | |||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Died | Recovered | |||||||||

| Off. | Enl. | Off. | Enl. | Off. | Enl. | Off. | Enl. | |||

| Commodore Tatnall's Flotila, S.C. | Jan 28, 1862 | 0 | ||||||||

| Battery Vulcan, SC | Feb 4, 1862 | 0 | ||||||||

| Fort Pulaski, GA | Apr 10-11, 1862 | 0 | ||||||||

| Tybee Island, GA | Aug 5, 1862 | 0 | ||||||||

| Skull Creek, SC | Sept 24, 1862 | 0 | ||||||||

| Bluffton and Crowell's Plantation, SC | Sept 30, 1862 | 1 | 1 | |||||||

| Elba Isalnd, SC | Oct 1, 1862 | 0 | ||||||||

| Kirk's Bluff, SC | Oct 18, 1862 | 1 | 1 | |||||||

| Choctawhatchee River, SC | Oct 22, 1862 | 0 | ||||||||

| Bluffton, SC | June 4, 1863 | 0 | ||||||||

Charleston, South Carolina (1863)

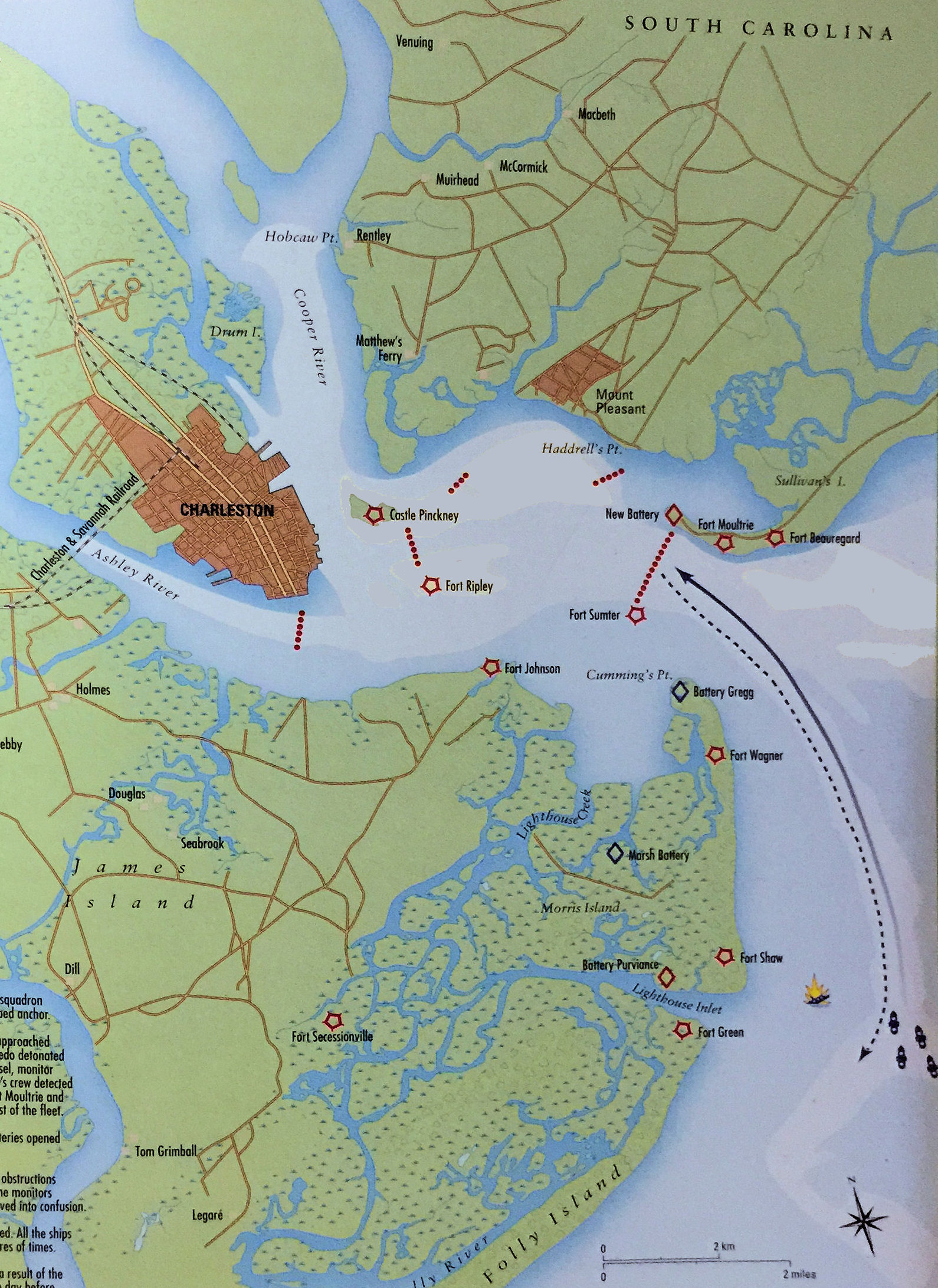

Because the Civil War began with the Confederate troops firing on Fort Sumter in Charleston Harbor, both the fort and Charleston were symbols of the war. Besides being symbolic, the harbor was an important port that continued to supply the Confederates with much needed guns, ammunition and supplies from Europe despite the Federal blockade. The Federals desired to capture Fort Sumter and take control of Charleston Harbor.

The harbor of Charlestown was protected by strong Confederate fortifications. The main channel to the harbor passed directly between Fort Moultrie to the north on Sullivan’s Island and Fort Sumter to the south. Sullivan’s Island was fortified with Fort Beauregard to protect the eastern approach to Fort Moultrie and by four additional sand batteries to defend the obstructions placed in the channel between Fort Moultrie and Fort Sumter. The southern approach to Fort Sumter was protected by Fort Wagner and Battery Greg on Morris Island. Closer to the city, Fort Johnson, Fort Ripley, Castle Pickney and other batteries protected the harbor.

The harbor of Charlestown was protected by strong Confederate fortifications. The main channel to the harbor passed directly between Fort Moultrie to the north on Sullivan’s Island and Fort Sumter to the south. Sullivan’s Island was fortified with Fort Beauregard to protect the eastern approach to Fort Moultrie and by four additional sand batteries to defend the obstructions placed in the channel between Fort Moultrie and Fort Sumter. The southern approach to Fort Sumter was protected by Fort Wagner and Battery Greg on Morris Island. Closer to the city, Fort Johnson, Fort Ripley, Castle Pickney and other batteries protected the harbor.

On April 7, 1863, a fleet of nine Federal ironclad vessels attacked Fort Sumter. The fight soon involved the Confederate ironclads and all the Confederate fortifications that could fire on the fleet. Both sides sustained damage. The damage to the Federal ironclads was severe enough that Rear Admiral Du Pont decided not to endanger his fleet by continuing the attack the next day. It was apparent that Charleston would not be captured by naval action alone, but would required a combined sea and land attack.

The Federal army then planned to land on Folley Island, establish a base, then cross a narrow river to Morris Island where they would capture Fort Wagner. From there, they could destroy Fort Sumter.

During the evening of June 18, 1863, orders were telegraphed to the Union troops at Fort Pulaski, South Carolina. The 48th Regiment of New York was to prepare to depart. On June 20, Companies G and I of the 48th Regiment remained at Fort Pulaski on garrison duty while the other companies steamed on the ship Ben De Ford toward St. Helena Island, off the coast of North Carolina. At St. Helena Island, the 48th Regiment joined other regiments. On July 4, the group collectively known as “Strong’s Fighting Brigade” landed on Folley Island.

Four days later, the Brigade prepared to board the boats that would be rowed to the adjacent Morris Island. For some reason, they returned to camp without loading the boats.

At 3:00 pm on July 9, the brigade again assembled and marched to the boats. The first assault on Morris Island by the 48th Regiment of New York included Companies A, C, D and F under Lieutenant-Colonel James M. McGree. The remainder of the brigade under Colonel Barton marched to the rear to wait for the boats to return the next morning.

Silently in the stillness of the night, Strong’s brigade packed closely in the boats and escorted by four howitzer launches manned by sailors, rowed up the Folly River and Creek to the entrance to Lighthouse Inlet, and halted. "We were thoroughly masked by tall march grass, and so noiselessly did the little flotilla move, that we were unheard and unobserved by the enemy. There we rested on our oars the whole night through awaiting the signal to advance, fearful every moment that we would be discovered by the sentinels on Confederate works, which frowned upon us from across the inlet."

No one who remembers the sensations that night will ever forget them: the sailors who rowed the boats seemed tranquil enough, being more at home on the water, but the soldiers preferred to have terra firma under them when they fought; the anticipation of having the boat you are in blown to pieces by a shell, and yourself, loaded down with cartridge-box and accoutrements, precipitated into the water and drowned, was not exhilarating. To face the perils of the water as well as the perils of batteries to front and to anticipate it a long night through, put the courage of the men to a strain, but did not break it.

A perfect silence reigned all about us that night; the screeching of a sea-fowl as it flew over our head, the breaking of a twig by some careless foot on the shore, the gentle swash of the sea against the sides of the boats and the beating of our own hearts, were all the sounds were heard. Hours passed, and not a word was spoken. We knew the batteries were ready on Little Folly Island, that they would be unmasked at the first peep of the day, that with the firing of their first guns we would be rowed rapidly across that six hundred yards of water that was between us and the beach of Morris Island in our front. Whether we should ever reached it was what we did not know; and we all feared a deal more that we might be drowned in the inlet, than any danger we should meet from the batteries when once our feet were on the shore .(Palmer)

As the sun rose on July 10, the Federal batteries on Folley Island and four ironclads offshore opened fire. About half past six, the boats which held the 48th Regiment were signaled to advance. Twenty minutes later, the landing party was crossing the river. One boat had been sunk by gun fire. By ten o’clock that morning, the Federals had taken control of two-thirds of Morris Island. General Strong ordered a halt just out of range of Battery Wagner to rest and bring up reinforcements.

| Place | Date | Killed | Wounded | Missing | Total | |||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Died | Recovered | |||||||||

| Off. | Enl. | Off. | Enl. | Off. | Enl. | Off. | Enl. | |||

| Morris Island, SC | July 10, 1863 | 1 | 5 | 19 | 25 | |||||

The next day, an assault against Fort Wagner on the island was repulsed by the Confederates. Three additional regiments joined the another attack on July 12, but again it failed miserably. Thereafter, General Strong decided to erect Federal batteries on Morris Island. During the day, the Confederates fired upon the Federals, not only from Fort Wagner, but from Fort Johnson, Fort Sumter and Battery Gregg. By night, construction of the batteries continued. For most of the week, the Federals returned the fire with intermittent shelling from their batteries and from the ironclads.

| Place | Date | Killed | Wounded | Missing | Total | |||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Died | Recovered | |||||||||

| Off. | Enl. | Off. | Enl. | Off. | Enl. | Off. | Enl. | |||

| Morris Island, SC | July 14, 1863 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 2 | 5 | ||||

On July 18, the Federals were ready for a renewed attack. During the afternoon six ironclads, five wooden gunboats and the Federal batteries bombarded Fort Wagner. There was no return fire as the Confederates soldiers remained in the bombproof shelters within the fort. It appeared to the Federal soldiers, that the fort had been overwhelmed.

After dark, the firing was stopped, the Federal brigades formed line and moved up the sand. Leading the assault was the 54th Massachusetts, the famous first African-American regiment organized by the Union during the Civil War. They were followed by the 6th Connecticut and the 48th New York volunteers.

After dark, the firing was stopped, the Federal brigades formed line and moved up the sand. Leading the assault was the 54th Massachusetts, the famous first African-American regiment organized by the Union during the Civil War. They were followed by the 6th Connecticut and the 48th New York volunteers.

.jpg)

Once again, the Confederates were ready. Having survived the bombardment, they waited until the best time to open fire. At the fort, the island narrowed so that the assaulting column was forced to compact themselves to about a third of the normal length. The Confederates opened fire into the compact mass of Federal soldiers as they advanced. Some of the Federals crossed the moat in front of the fort and scrambled up the sandy slopes of the fort to participate in hand-to-hand fighting.

We crossed the moat and engaged in a hand-to-hand fight with the Thirty-first North Carolina in their outer works. They soon weakened, and we drove them from the southeast bastion, which we held under a terrible cross fire. Re-enforcements were sent to our support, but by some blunder, they mistook us for the enemy and poured a destructive volley into us. We could not live under the three fires, and something had to be done to stop the fire in our rear. I ran down into the moat and told our men there of the terrible blunder they were making and on this errand was shot in the elbow.

Having stopped the fire in our rear, I returned to the crest of the fort to find Color-Sergeant George G. Sparks, severly wounded, the color staff shot in two, and all the color-guard either killed or wounded. I picked up the colors with my uninjured hand, but just at that moment the Confederates made a determined assault on us. We managed to repulse the assault, but I received two additional wounds; the bone of my left forearm was completely shattered, and I was wounded in the head by pieces of a shell that burst near me. My scalp was torn and the blood was running into my eyes.

Private Joseph C. Hibson

48th New York Infantry

Kagan, pg 97

In the end, the Federals were driven away. Of the ten regiments that participated in the attack, the four that suffered the greatest losses were the 54th Massachusetts (272), 48th of New York (242), the 7th New Hampshire (216) and the 100th New York (175) for a total of 905. Confederate losses were substantially less.

| Place | Date | Killed | Wounded | Missing | Total | |||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Died | Recovered | |||||||||

| Off. | Enl. | Off. | Enl. | Off. | Enl. | Off. | Enl. | |||

| Battery Wagner, SC | July 18, 1863 | 3 | 61 | 3 | 18 | 4 | 87 | 3 | 63 | 242 |

Having failed again, the Federals began a siege of the fort. By sunlight, they cowered in shallow sand trenches to avoid by the shells fired from nearby Confederate batteries and Confederate ironclads. By darkness, the Federal soldiers dug the trenches closer, advanced their batteries, obtained supplies and carried their wounded to safety.

The Confederate soldiers spent the days in bombproof shelters in the fort which were even less ventilated than the enclosed ironclads and made worse by the fact that they also served as hospitals for the wounded. After dark, when the bombing ended, they would work all night to repair the damage, receive water and supplies, and care for their wounded.

Each day the siege lines came closer and the fort looked more like a mound of sand. From July into September the siege continued. Finally, the Federals decided that a direct assault would be less costly than continuing the siege and made plans for another assault. However, the Confederates had concluded that Fort Wagner no longer served any purpose. Amid the cover of darkness of September 6, the garrison was withdrawn. Morris Island was now under federal control.

Morris Island ceased to matter in strategic importance long before it fell to the Federals. While the siege was in progress, other batteries had been built by the Federals that could fire directly into Fort Sumter. These included Marsh Battery which contained the "Swamp Angel" artillery piece. It was one of the most famous artillery pieces used during the Civil War. It was a new weapon, an eight-inch barrel rifled cannon with greatly increased accuracy and range.

Gillmore decided to use long range rifled heavy artillery to reduce Fort Sumter, a tactic that had proved successful at Fort Pulaski, Georgia in April of 1862. Gilmore had several pieces of heavy artillery, as well as mortars, to shell not only Fort Sumter, but also other Confederate defensive positions and the city of Charleston itself.

To that end, Gillmore instructed Colonel Edward W. Serrell of the 1st New York Engineers to search for a location in the swamps and salt marshes between James and Morris Islands suitable for the construction of a battery from which long-range artillery could fire on the city. Gilmore carefully scouted various locations and found one about 7900 yards from Charleston that appeared to be suitable for building a battery capable of holding a large rifled gun.

With assistance from the 7th New Hampshire Infantry, the engineers went to work. To construct the battery’s parapet, pilings were driven into the mud, and a platform of log crossbeams was attached to the pilings. This platform was covered with 13,000 sandbags hand carried across a 1,700-foot wooden causeway by the men of the 7th New Hampshire. After completing the parapet, a wooden platform was constructed for the gun itself that was detached from the parapet. The two sections essentially floated on the surface of the marsh. On August 17th, an eight-inch Parrot rifle and carriage weighing about 24,000 pounds was successfully transported to the site and mounted in place in what was called the Marsh Battery. It was a remarkable engineering accomplishment under difficult conditions. The men named the huge gun the “Swamp Angel”.

https://ironbrigader.com/2012/05/15/swamp-angel-charleston-south-carolina-1863/

Day after day projectiles from the batteries and ironclads damaged sections of Fort Sumter. Night after night, the Confederate troops repaired the damage. By the end of August, only one gun remained operational at the fort. It defiantly fired the salute to the Confederate flag every day.

Although Morris Island was captured and Fort Sumter was damaged to the point of uselessness, the Federals were still no closer to Charleston. While the bombardment of Fort Sumter was taking place, Beauregard took most of the guns from the fort and redistributed them among the other batteries guarding the inner harbor. Any Federal craft that entered the harbor received heavy fire. Charleston was still protected.

After the assaults on the beach and the two assaults on Fort Wagner, the 48th Regiment of New York was only a shattered remnant of its former self. Christopher himself was hit with a minnie ball in the left leg during the charge of the fort. On July 22, while the siege was in progress, they received orders to sail to Hilton Head, South Carolina. They did not see the eventual capture of the fort for which so many of their own gave their lives.

After the assaults on the beach and the two assaults on Fort Wagner, the 48th Regiment of New York was only a shattered remnant of its former self. Christopher himself was hit with a minnie ball in the left leg during the charge of the fort. On July 22, while the siege was in progress, they received orders to sail to Hilton Head, South Carolina. They did not see the eventual capture of the fort for which so many of their own gave their lives.

In August, the 48th Regiment of New York was sent to St. Augustine, Florida for garrison duty. They were relieved October 4 and returned to Hilton Head on the sixth. For the next two months, the company’s muster rolls recorded that Christopher Harbison was “absent on recruiting drive”, probably meaning at home recuperating.

Jacksonville, Florida (1864)

By 1864, Union control of the seceded state of Florida was a new strategic target. In the Presidential election year, a southern state sufficiently occupied by Union forces would not only demonstrate the strength of the Union power, but allow the state to send a pro-Union candidate to the upcoming presidential nomination convention.

Florida appeared to offer better prospect of success in such an undertaking than any other Southern State. Its great extent of coast and its intersection by a broad and deep river, navigable by vessels of war, exposed a great part of the State to the control of the Union forces whenever it should be thought desirable to occupy it. (Yoseloff, p. 76)

.jpg) In 1864, little resistance to Union occupaction was anticipated in Florida because many of the Confederate troops were deployed elsewhere. On February 5, General Truman Seymour of the Union army steamed with troops from Hilton Head to Jacksonville, Florida. Among those on the steamer Delaware was Company D. Jacksonville had been occupied briefly by the Union in the spring of 1862, October 1862, and most recently in March 1863 for a few months.

In 1864, little resistance to Union occupaction was anticipated in Florida because many of the Confederate troops were deployed elsewhere. On February 5, General Truman Seymour of the Union army steamed with troops from Hilton Head to Jacksonville, Florida. Among those on the steamer Delaware was Company D. Jacksonville had been occupied briefly by the Union in the spring of 1862, October 1862, and most recently in March 1863 for a few months.

On February 7, 1864, General Seymour’s force of about 7,000 men landed at Jacksonville. According to Catton, “white and black troops were brigaded together” (Catton, New History of the Civil War, pg. 404). No opposition was met. Since it was known that the Confederate forces were widely scattered, it was decided to press inland as much as possible. The plan was to push west 60 miles along the Atlantic and Gulf Central Railroad to the Suwannee River, severing the Confederate supply routes and recruiting black soldiers for the Union army along the way.

By February 9, Union forces reached the town of Baldwin. By the eleventh, the main force had reached Barber’s Plantation, about 12 miles inland from Jacksonville along the railroad. The Union forces were counting on the railroad to keep their troops supplied. Upon reaching it, however, they found only one inoperable engine. So the expedition continued on foot another nine miles along the railroad to Sanderson and continued on foot for another forty miles. There General Seymour’s force received reports of Confederate forces amassing up ahead. With his own supply problems, they returned eastward to Barber's Plantation.

By February 9, Union forces reached the town of Baldwin. By the eleventh, the main force had reached Barber’s Plantation, about 12 miles inland from Jacksonville along the railroad. The Union forces were counting on the railroad to keep their troops supplied. Upon reaching it, however, they found only one inoperable engine. So the expedition continued on foot another nine miles along the railroad to Sanderson and continued on foot for another forty miles. There General Seymour’s force received reports of Confederate forces amassing up ahead. With his own supply problems, they returned eastward to Barber's Plantation.

Once there, General Seymor decided that Barber’s Plantation was not a defensible position. His intellegence also led him to believe that the Confederate forces were now equal in strength to his own troops, having obtained reinforcements from Charleston and Savannah. General Seymor had to decide whether to retreat eastward or proceed westward to meet the enemy.

Accordingly, on February 20, 1864, Union forces, including Company D, marched westward along the railroad. Approximately three miles east of Olustee Station, Confederate troops met them in the only major battle in Florida. It began in the morning and lasted about four hours in open pine woods. Momentum shifted back and forth. The Union line began to give up ground reluctantly at first. Eventually, the withdrawal became a full-scale retreat. Confederate pursuit continued until nightfall. The battle, also known as Ocean Point, engaged 5,500 Union forces against 5,200 Confederates. By night the losses to the Union forces were 203 killed, 1,152 wounded and 506 missing for a total of 1,861, or 34 percent of their total force. Confederate losses totaled 934, of which 93 were killed and 841 were wounded, or 18 percent of their total force. Union forces retreated to Jacksonville.

Afterward, Company D embarked on the steamer Maple Leaf on March 9 for Palatka, located upstream from Jacksonville on the St. John's River. There they made earthworks and batteries in the rear of the town. The gnats were more of a problem than the Confederates. For about a month, Company D remained at Palatka until they returned to Hilton Head Island.

| Place | Date | Killed | Wounded | Missing | Total | |||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Died | Recovered | |||||||||

| Off. | Enl. | Off. | Enl. | Off. | Enl. | Off. | Enl. | |||

| Sanderson, FL | Feb 12, 1864 | 1 | 1 | |||||||

| Oulstee, FL | Feb 20, 1864 | 1 | 38 | 10 | 1 | 143 | 22 | 215 | ||

| Near Palatka, FL | Mar 17, 1864 | 0 | ||||||||

Army of the James (1864)

Virginia was always a focal point of the Federal attack during the Civil War. On April 9, 1864, General Ulysses S. Grant issued orders for a combined campaign to capture Richmond, Virginia. Major General Sigel would move down the Shenandoah Valley in Virginia from the west, General Benjamin Butler and the Army of the James would move from the south and the General Grant and the Army of the Potomac would advance against General Lee and the Confederate Army of Northern Virginia from the northeast.

Company D of the 48th Regiment of New York Volunteers had been stationed in Palatka, Florida since the beginning of March 1864. On April 16, they embarked on the steamer Ben De Ford and traveled to Hilton Head Island, South Carolina. Four days later they sailed to Fortress Monroe, Virginia to join with twenty-two other regiments to form the Army of the James. By the twenty-third, they landed at Gloucester Point on the York River in Virginia. Here, Christopher Harbison was promoted on April 28, 1864 to the rank of sergeant.

Throughout the following campaigns of Company D, quotes are taken from the diary of Christopher Harbison. These entries are entitled “Campaign in Va.” A roster of Company D from that diary is available in Appendix A.

May the 4th. Started from Gloucester Point in steamer Delaware in Company with the 10th Corps (Harbison)

On May 4, the steamer Delaware sailed down the York River to Fortress Monroe and up the James River to a location called Bermuda Hundred.

.jpg) By the fifth, the entire Army of the James had landed at Bermuda Hundred and City Point. Bermuda Hundred was at the tip of a peninsula formed by the Appomattox River to the south and the James River to the north and east. City Point was on the south shore of the Appomattox River.

By the fifth, the entire Army of the James had landed at Bermuda Hundred and City Point. Bermuda Hundred was at the tip of a peninsula formed by the Appomattox River to the south and the James River to the north and east. City Point was on the south shore of the Appomattox River.

5th assended the James R as far as City Point. At 12 ½ landed & lay on shore killing & waiting until about 12 o’clock in the M When we start on the march, halted & made coffee about 8 o’clock (Harbison)

Strategically, it appeared that the Army of the James would have little difficulty in achieving their objectives. They planned to capture a portion of the Petersburg-to-Richmond Railroad, disrupting communication lines, and hindering vital food and troop reinforcements for Richmond. Within the fifty-mile area around Petersburg and Richmond less than 10,000 Confederate troops were thought to oppose the Army of the James that numbered 39,000. Therefore, they should have been able to accomplish their goals and join General Grant’s advance on Richmond.

The Army of the James was hindered by what some authors believe to have been extreme caution on the part of the Union Command caused by defeats at Bull Run and other battles against entrenched defenders. General Butler also had limited military knowledge, although he was very influential in Union politics. He saw this command as his chance to earn the military distinction he wanted. General Grant, compelled to use him because of his policital connections, attempted to minimize potential problems by providing him with two experienced corps commanders.

On the night of the Bermuda Hundred landing, General Butler proposed to his corps commanders that the men immediately march toward Richmond "midnight or not." They advised him against such an advance. It would be foolish to advance in the dark and through unknown territory against an enemy whose position and strength were unknown. This would be the only time Butler accepted advice from his commanders.

The Federal forces instead built a defensive line of entrenchments across the peninsula while gunboats in both rivers protected their flanks. The following day, the first of many attempts was made to seize the railroad to Richmond. For some reason, the 10th Corp, under command of General Gillmore made no advance at all. Major General Smith sent one brigade which retreated after a skirmish with a few Confederates.

Another attempt was made to destroy the railroad. Union forces held a station briefly before Confederate troops, numering less than a third of the Union troops, forced them to withdraw back to their entrenchments. The campaign was beginning to be known as a “stationary advance.”

7th Marched out to Railroad & attacked the Rebs. May 7th fought the Battle of Chesterfield Station (Harbison)

On May 9, General Butler again ordered his troops out of the entrenchments to destroy the railroad. General Gillmore’s forces reached the railroad but suspended the railroad destruction to reinforce Smith's troops who were under attack. Little damage was done to the railroad. That afternoon, 14,000 Federal forces attempted to find and overcome the 100 Confederate troops in the area. Skirmishes were fought at Fort Clifton, Ware Bottom Church, Brandon (or Brander’s Bridge), Swift Creek and Arrowfield Church. Confusion prevailed in the Union forces. General Butler ordered the troops to withdraw to the entrenchments, apparently not realizing the importance of maintaining control of the railroad.

General Butler then decided to take the battle toward Richmond. On May 12, fifteen regiments, including the 48th Infantry of New York, began to move toward Fort Darling, located on Drewrey’s Bluff just south of Richmond. The Union forces spent the day laboriously getting into position. On the fifteenth, Butler planned an attack, but again was occupied in arranging a defensive position. In one of the few recorded instances of the war, telegraph wire was strung between tree stumps about a foot off the ground in the hope of tripping advancing enemy troops.

On the morning of the sixteenth, Confederate forces launched an attack against the Federal forces at Drewry’s Bluff. Five charges against the Federal’s right side were repulsed before it was overwhelmed. Fighting on the left was inconclusive and the center position held. The wire entanglements worked well, but the Federals did not hold their position. Instead they retreated to Bermuda Hundred, where they arrived safely the next day.

May the 16th fought the Battle of Drureys Bluff (Harbison)

So on May 17, 1864, the Army of the James was back at Bermuda Hundred, having acheived nothing of importance since landing on May 5. The minor damage to the railroad had been repaired. The Confederates had obtained reinforcements and fortified their position along the Federal entrenchments by building their own defensive works.

Minor skirmishes occurred on the eighteenth at Foster’s Plantation and at City Point. Skirmishes continued throughout the week.

May 19th fought the Rebs in Rifle Pits near our entrenchments (Harbison)

The Federals were now pinned by the James River to the north and east, the Appomattox River to the south and the Confederates to the West. General Butler had effectively lost his orgiainal advantage of position and numerical superiority. Some described the position at the time as being “corked in a bottle.” The potentially dangerous threat to the Confederate army around Richmond had been stopped.

| Place | Date | Killed | Wounded | Missing | Total | |||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Died | Recovered | |||||||||

| Off. | Enl. | Off. | Enl. | Off. | Enl. | Off. | Enl. | |||

| Port Waithall, VA | May 6-7, 1864 | 6 | 1 | 4 | 79 | 90 | ||||

| Proctor's Creek, VA | May 12, 1864 | 0 | ||||||||

| Drewry's Bluff, VA | May 14-16, 1864 | 1 | 8 | 15 | 24 | |||||

| Bermuda Hundred, VA | May 18 - 26, 1864 | 0 | ||||||||

| Other | 1 | 1 | ||||||||

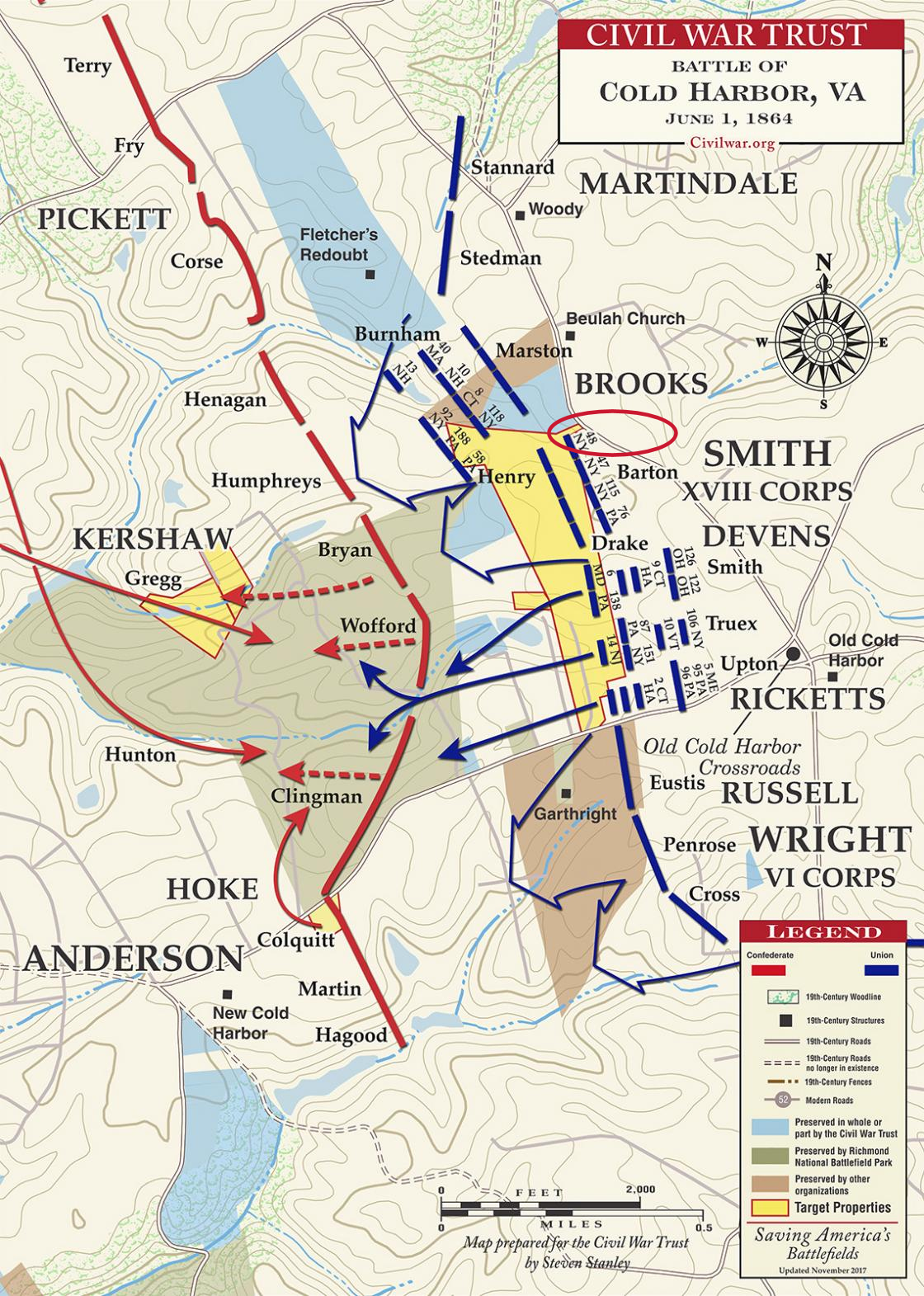

Army of the Potomac (1864)

Earlier, on May 4, 1864, the Fedferal Army of the Potomac, commanded by General Grant moved against the Confederate Army of Northern Virginia. The Army of the Potomac, with 122,000 troops, crossed the Rapidan River in Virginia. The Army of Northern Virginia commanded by General Lee had about 66,000 troops. For more than a month, the armies fought almost daily. General Lee anticipated the moves of the Federal troops and thus was able to position his army accordingly to stop any advancement into Virginia.

To the south of Richmond, General Butler’s troops were bottled in their defensive fortifications at Bermuda Hundred. The Confederate forces had built a line of entrenchment just to the west of the Union one. General Grant understood that the position was a stalemate and ordered a number of troops to be transferred from the Army of the James to the Army of the Potomac. Company D of the 48th Regiment of New York was one company that was included in the transfer.

May the 28th left South Side of the James for Petomac in Co with 18 Corps. (Harbison)

The selected troops under the command of Major General William F. Smith, marched to City Point and embarked on the steamer Delaware. The following day, they proceeded down the James River. By May 31, they landed at a point known as White House on the Pamunkey River. All night and through the heat and dust of the next day they marched to join the Army of the Potomac at Cold Harbor.

.jpg) On the morning of June 1, 1864, the Army of the Potomac had arrived at Cold Harbor, only to find that once again the Confederate troops had arrived earlier and were making entrenchments. Federal troops attacked but two charges were repulsed. Company D arrived at Cold Harbor late in the afternoon.

On the morning of June 1, 1864, the Army of the Potomac had arrived at Cold Harbor, only to find that once again the Confederate troops had arrived earlier and were making entrenchments. Federal troops attacked but two charges were repulsed. Company D arrived at Cold Harbor late in the afternoon.

Within half an hour, they were ordered to join the attack although they had just marched 25 miles. At 6 p.m. the Union forces, including Company D, advanced. General Smith’s troops rushed over the open field and captured the first line of Confederate rifle pits. They assaulted, but did not capture the second line. Both armies entrenched during the night.

Within half an hour, they were ordered to join the attack although they had just marched 25 miles. At 6 p.m. the Union forces, including Company D, advanced. General Smith’s troops rushed over the open field and captured the first line of Confederate rifle pits. They assaulted, but did not capture the second line. Both armies entrenched during the night.

June 1st fought the first battle at Cold Harbour (Harbison)

A renewed attack was planned by the Federals for the following morning, but troop movements, ammunition problems and fatigue postponed it. However, several skirmishes did erupt that morning.

June 2nd was wounded in the finger in Rifle Pits and C Harbor (Harbison)

Christopher eventually had the ring finger of his left hand amputated.

At Cold Harbor, rain that evening further postponed the attack. The main attack at Cold Harbor took place the next day, June 3.

Grant has determined to make a decisive blow on Lee’s army, hammering this line in a direct assault…. The charge is to be led by the corps of Hancock, Wright and Smith, later to be reinforced by Warren and Burnside, on the center and right of Lee’s line under Anderson and Hill. The attack is intended to be pressed regardless of the cost. It begins at 4:40 in the morning, countless thousands of Union soldiers rising from their entrenchments and marching straight toward the fortification of the enemy. Then, ‘there rang out suddenly on the summer air such a crash of artillery and musketry as its seldom heard in war.’ The dead and wounded fall in waves like mown wheat. For a short time, the Confederate breastworks are reached, but then a murderous countercharge sends the Federals back.

Within the space of half hour 7,000 Federal troops are killed and wounded, their bodies blanketing the ground before the enemy breastworks…. Incredibly, after the devasted troops have fallen back from the first attack, the order comes from Grant for a second general assault… This charge is mounted raggedly, with many troops holding back, and it is repulsed, leaving fresh heaps of dead and wounded. Finally, Grant orders a third advance. This order is essentially ignored. . . When Grant calls off the attack at noon, Federal killed and wounded for 3 June total around 7,000, added to the 5,000 casualties of 1 and 2 June. The Confederal losses are probably under 1,500. (Bowman, p 206)

The 48th Regiment continued to fight skirmishes on June 4, June 5, June 8 and June 12. During this time, the apposing armies laid in their respective entrenchments, hardly moving at all.

| Place | Date | Killed | Wounded | Missing | Total | |||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Died | Recovered | |||||||||

| Off. | Enl. | Off. | Enl. | Off. | Enl. | Off. | Enl. | |||

| First Assault, Cold Harbor, VA | June 1, 1864 | 1 | 10 | 3 | 4 | 56 | 74 | |||

| Cold Harbor, VA | June 1 - 12, 1864 | 1 | 4 | 5 | ||||||

This campaign, and especially the first six weeks of it, from May 5 to June 18, 1864 witnessed the most relentless fighting and the cruelest carnage of the war, culminating in a prolonged stalemate in the trenches before Petersburg and Richmond that anticipate the Western Front in World War I. Historians have often described these events as ‘Grant’s campaign of attrition’ to grind down the Confederates with superior numbers and resources. . . The campaign turned out to be one of attrition, but that was more Lee’s doing than Grant’s. The Union commander intended to maneuver Lee into a position for open-field combat; Lee parried these efforts from elaborate entrenchments with the hope of holding out long enough to discourage the Northern people and force their leaders to make peace – a strategy of psychological attrition. It almost worked, but Lincoln’s reelection and Grant’s determination to stay the course brought victory in the end. (McPherson, pg 113)

June the 8th went to Corps Hospital. (Harbison)

June the 9th Marched to Whitehouse where lay in Hospital two days (Harbison)

June the 11th took Steamer N.Y. for Bermuda Hundereds & went in Hospital at Point of Rocks (Harbison)

Being wounded, Christopher went to the Union stronghold at Bermuda Hundred, Virginia. The Army of the Potomac would eventually cross the Appomattox River to place Petersburg, Virginia under siege. Christopher, however, began his long journey home. He was discharged June 1, 1864. Christopher returned to farming in New Jersey and married Sallie Horner approximately two years later.

Reunion

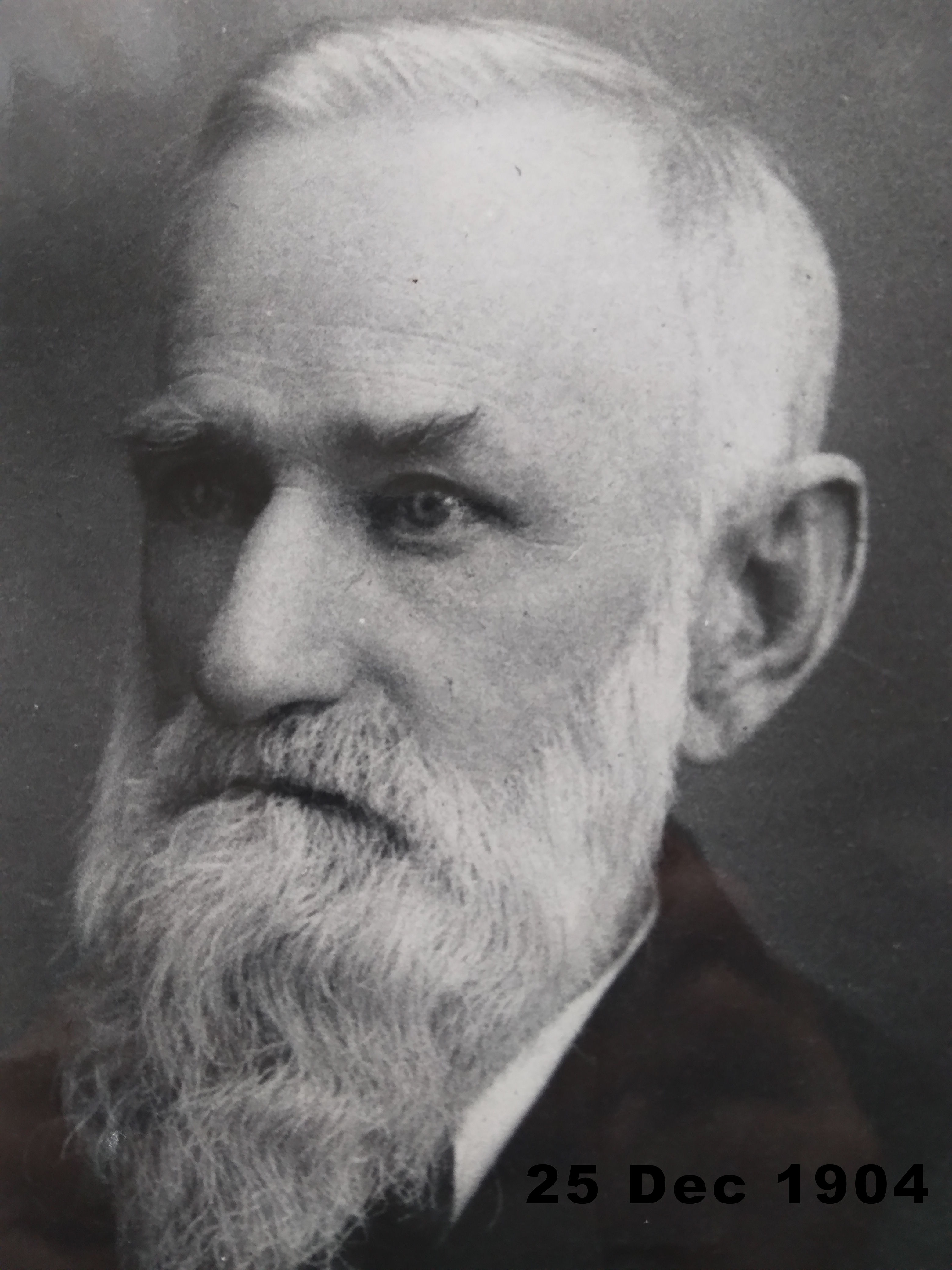

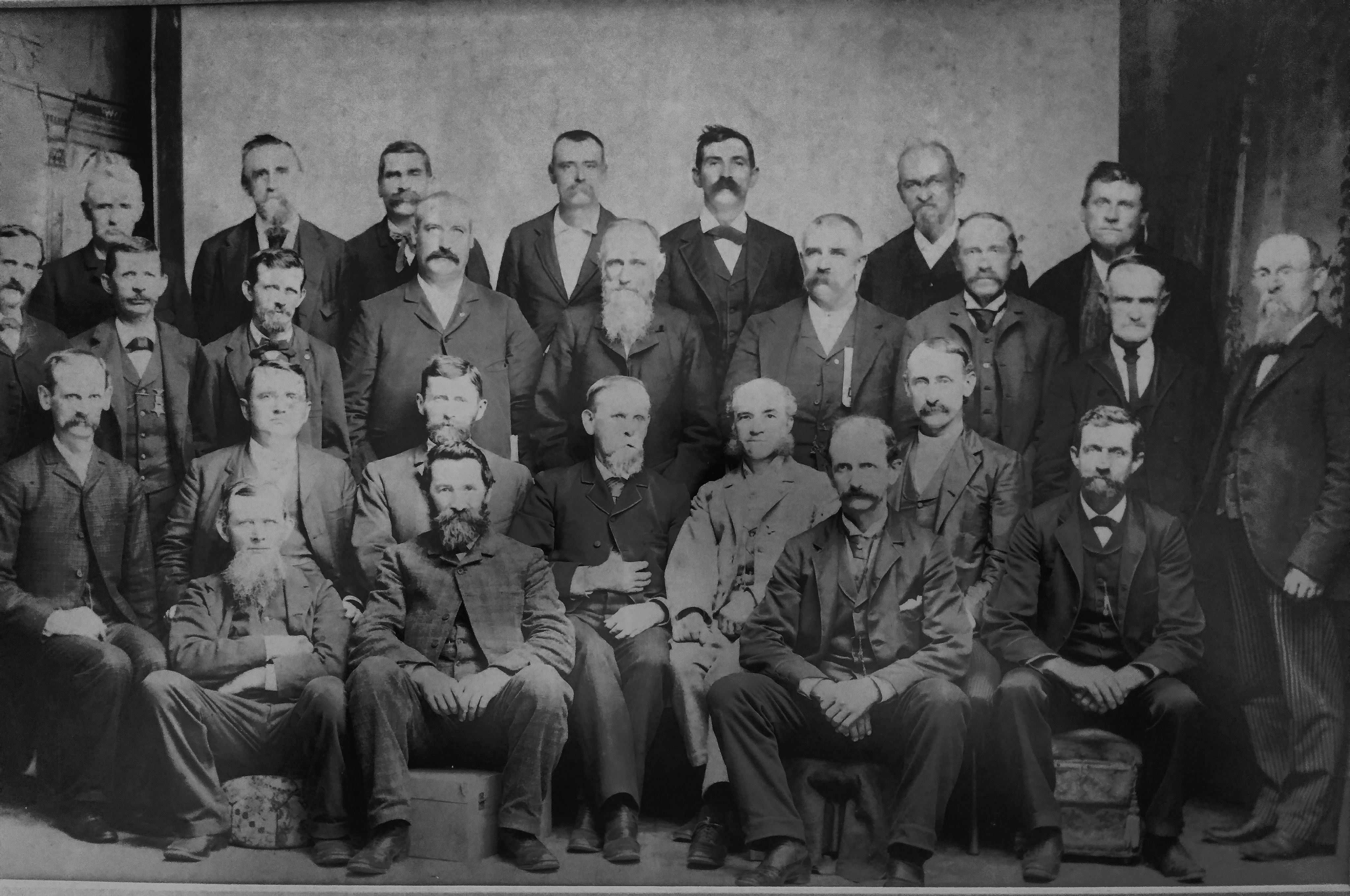

Christopher Harbison portrait in 1904. It is believed that the group picture was taken during a reunion of Company D of the 48th New York, date unknown. Christopher Harbison is at the center of the second row from the top.

Bibliography

Bowman, John, S. Editor; The Civil War Almanac; Bison Books Corp.; New York, New York; 1982.

Catton, Bruce; New History of the Civil War; ibooks, inc; New York; 1996.

Catton, Bruce; Never Call Retreat Washington Square Publication; New York, New York; 1965.

Catton, Bruce; Terrible Swift Sword; Doubleday & Company; Garden Gity, New York; 1963.

Commanding Officer of the 48th Regiment of New York; Christopher C. Harbison promotion certificate; in possession of author; 1864.

Editors of Time-Life Books; Voices of the Civil War - Charleston; Time Life Books; Alexandria, Virginia; 1997.

Gillmore, Brig. Gen. Quincy A.; The Siege and Reduction of Fort Pulaski; Thomas Publications; Gettysburg, Pa; 1862, reprinted 1988.

Harbison, Christopher; Personal Diary; unpublished; 1864.

Long, E. B.; The Civil War Day by Day; Doubleday & Company, Inc.; Garden City, New York; 1971.

MacDonald, John; The Historical Atlas of the Civil War; Chartwell Books, Inc.; 2009.

McPherson, James; This Mighty Scourge, Perspectives on the Civil War; University Press; New York, New York; 2007.

Palmer, Abraham J., D. D.; The History of the Forty-Eight Regiment, New York State Volunteers in the War for the Union, 1861 - 1865; Veteran Associations of the Regiment; Brooklyn, N.Y.; 1885. (Peabody Library 973.7447)

Phisterer, Frederick; New York in the War of the Rebellion 1861 – 1865; Weed, Parsons and Company; Albany; 1890.

Rhea, Gordon C.; Cold Harbor: Grant and Lee, May 26 - June 3 1864; Lousiana State University Press; Baton Rouge; 2002.

State of New York: Adjunct General's Office; A Record of the Commissioned Officers, Non-Commissioned Officers and Privates of the Regiments Which Were Organized in the State of New York...; Vol II; Comstock & Cassidy Printers; New York; 1864.

State of New York, Adjutant-General’s Officer; U. S.Civil War Muster Roll Abstracts; 1861-1865. (https://search.ancestry.com/search/db.aspx?dbid=1965, pg. 1134-1135)

State of New York, Adjutant-General’s Officer; U. S. Civil War Soldier Records and Profiles; 1861-1865. (https://search.ancestry.com/search/db.aspx?dbid=1555)

Yosekoff, Thomas; The Way to Appomattox, Battles and Leaders of the Civil War; Volume IV; New York; 1956.